Look inward: that which is most personal is most universal.

Hosted free by tripod.com

One Sky Above Us

last save 10/23/09

Primordial North American Spirituality

That Which Is

Most Personal

Is Most Universal

In pride, in reas'ning pride, our error lies;

All quit their sphere, and rush into the skies!

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of mankind is man.

[Alexander Pope. Essay on Man]

We Need to Look Inward to Find the Truth

by Robert Shepherd

Have we quit our sphere and rushed into the skies? Isn't this not what man has done with religion? Where the core of our concern is properly "anthropology" -- we rather have put in its place a distant THEOLOGY. I mean no disrespect to wholesome religion or spirituality. But if we go back to beginnings, we may discover that the best wisdom is what is nearest at hand.

homo sum: human nihil a me alienum puto (I am a man, and nothing human is alien to me)

Martin Buber emphasized that in Judaism, the focus was essentially this-worldly. What Christendom did, when it articulated and systematized a theology, was to elevate religion to a pie-in-the-sky realm, all too far removed from the humble soil of this life on earth. They erected an elaborate theological edifice, far removed from the humble this-worldliness of Genesis, with its tribal duties, and familial life, and essential anthropology. Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, scripture commands us. (Where did we lose that?)

After a dozen generations as a tiny, persecuted sect; Then as a suspicious minority religion, Christianity finally traded places with its former persecutors, and became the official established religion of the Empire. A governing body of scholar-priests set about defining and elaborating "correct" beliefs and doctrines. As they did so, Christianity became more and more intricate, layered, and officially, at least, hardened. As details were defined, issues, ironically, became more convoluted, circuitous, complex. Aboriginal truth, which had been more primitive, yet at the same time more emphatic and direct, soon found itself clothed in an unrecognizable raiment. The simple gospel with its hebraic and judaic character found itself arrayed in a fancy new dress only remotely reminiscent of its authentic shemitic roots.

As a young man I came under the instruction of a Cherokee preacher (Bishop Whitlock) who liked to say, "Jesus didn't teach go-to-heaven; he taught kingdom-of-heaven." Whitlock believed that the "promised land" would be this-worldly, right here on earth. He rejected the eschatology of a "rapture" and instead said our eyes must be opened to truly "see Jesus."

Interestingly, I think the Bible, even if the main Hebrew focus was this-worldly, nevertheless offers the hope of an unseen world. I believe the Bible holds out the promise of a REWARD for our labors. As with any pursuit, there is a spiritual principle of persistence. Ask and it shall be given you; seek and ye shall find; knock and it shall be opened unto you.

Whitlock, like Thomas Jefferson, like Leo Tolstoy and others, directed our attention to the teachings of Jesus. The answer is in the red letters (the teachings of Jesus). A hurdle I am trying to overcome is the fact that, steeped in the heritage of European Christianity, I believe I lost sight of the essential Semitic and Jewish character of the words of Jesus.

We know that the Christian religion was grafted on to something far older. The stock of "the olive tree" had roots deep into Shemitic and Cushitic and Hebraic soil. It certainly was not European in its origins. Why are we shocked that so-called white-man's religion (in reality) is anything but.

Jesus Christ, in so many ways, seems to be the absolute hinge-point of history. For example, he divided hebraic and pagan, for one thing. Paganism, with divergent myths and symbolism, points forward as if to predict this "dying god" (hero or redeemer).

Christianity did not destroy paganism; it adopted it

Will Durant goes even further, declaring "The Greek mind, dying, came to a transmigrated life in the theology and liturgy of the Church . . . the Greek mysteries passed down into the impressive mystery of the Mass. Other pagan cultures contributed to the syncretistic result. From Egypt came the ideas of a divine trinity . . . from Egypt the adoration of the Mother and Child, and the mystic theosophy that made Neo-Platonism and Gnosticism, and obscured the Christian creed . . . From Phrygia came the worship of the Great Mother; from Syria the resurrection drama of Adonis.

Christianity was the last great creation of the ancient pagan world."

Saint Augustine of Hippo had written:

"That which is now called the Christian religion existed among the ancients, and never did not exist from the planting of the human race until Christ came in the flesh, at which time the true religion which already existed began to be called Christianity."

Why should this not be? To quote Paul Clasper,

"The myths which have kindled the imaginations of the peoples have come to be seen as a special 'Preparation for the Gospel.' They are natural 'points of contact' for the Christian message.

One myth has been nearly universal and so of special importance. This is the story of the dying-rising God. In almost every culture there has been some variation on this basic myth-theme. Through carelessness and disobedience the land has been cursed; all is sick and out of joint. But the king, or his son or another representative, will pass through the darkness of death, there will then come new life to the world. The curse will be removed; spring will break forth and banish the bleakness of winter's death. Through a sacrificial death, resurrection life will come to the world. This was often given ritual expression in New year�s or spring festivals.

In our time it is C.S. Lewis, the brilliant Oxford and Cambridge Professor of Renaissance Literature and refreshing lay theologian, who has taken this subject most seriously. He gave a life-time of scholarly study to the myth-making capacity and its importance for our lives. More than almost anybody in his generation he helped to "unfreeze the imagination" so that truth-through-pictures could once again play its rightful place in our lives. He was speaking to a generation that had nearly lost the ability to use "the feeling intellect."

In his early days, before he became a Christian, he was fascinated with the place of myth and ritual in the life of Norse and Celtic cultures. Here he discovered the importance of this dying-rising God theme. He kept wondering where and how this originated, how it spread, and just why this particular myth came to mean so much to so many people. He described himself as one

"who first approached Christianity from a delighted interest in, and reverence for, the best pagan imagination, who loved Balder before Christ and Plato before St. Augustine."

In time he began rather nervously to wonder if this really was a true picture, and if it described something that really happened. His close friend at the time was J.R.R. Tolkien, author of the Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien was a believing, practicing Catholic Christian who also had a serious interest in myths and their relationship to the Christian faith. Tolkien gently suggested that the myth of the dying-rising God had actually happened and this was what Christians meant by the incarnation and resurrection of Jesus Christ. In time, C.S. Lewis found his old defenses against the Christian faith melting away. After a period he, too, became a Christian. Lewis brought to his life an abiding appreciation for the place of myth and imagination in human experience.

C.S. Lewis saw that the persistence of this major myth-theme was a part of God�s gracious calling, or luring, of the world back to the true way of life. In his Mere Christianity, Lewis wrote: God "sent the human race what I call good dreams: I mean those queer stories scattered all through the heathen religions about a god who dies and comes to life again and, by his death, has somehow given new life to men."

We need have no fear that to rejoice in these good dreams will destroy the uniqueness of the Gospel. Actually, it should have the opposite effect. It should be an encouragement and helpful confirmation of the Gospel. Lewis put it this way: "Christ is more than Balder, not less. We must not be ashamed of the mythical radiance resting on our theology. We must not be nervous about 'parallels' and 'pagan Christs': they ought to be there-it would be a stumbling block if they weren't." He wrote: "If my religion is erroneous, then occurrences of similar motifs in pagan stories are of course instances of the same or a similar error. But if my religion is true, then these stories may well be a preparatio evangelica, a divine hinting in poetic and ritual form of the same central truth which was later focused and (so to speak) historicized in the Incarnation."

This , of course, is the crux of the matter. In Jesus Christ, at a certain point in Roman history � under Pontius Pilate � there came a 'focusing and historicizing' of the great myth in the happening which Christians call the incarnation of Jesus Christ as the 'Word of God made flesh.' This is seen as the crucial (the word means 'cross') event at the center of the world and the turning point of history. From this time on there is B.C. and A.D. In Lewis words, 'the myth became fact.' But in becoming fact it did not despise or dispense with myth. Lewis wrote:

Now as myth transcends thought, incarnation transcends myth. The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the Dying God , without ceasing to be myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. It happens � at a particular date, in a particular place, followed by definable historical consequences. We pass from a Balder or an Osiris, dying nobody knows when or where, to a historical person crucified (it is all in order) under Pontius Pilate. By becoming fact it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle. I suspect that men have sometimes derived more spiritual sustenance from myths they did not believe than from the religion they professed. To be truly Christian we must both assent to the historical fact and also receive the myth (fact though it has become) with the same imaginative embrace which we accord to all myths. The one is hardly more necessary than the other is.

All of this is ripe material for in-depth academic inquiry (reminds me of Joseph Campbell's concept of the monomyth --

the Hero With a Thousand Faces).

For alternative discussion,

compare.

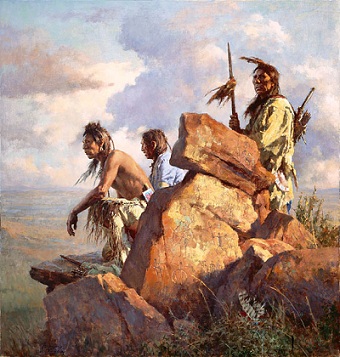

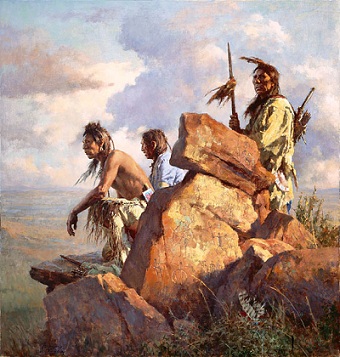

Among the Spirits of Long Ago

Howard Terpning

Martin Luther King reminds me to turn again to the Good Book, the scriptures esteemed in our biblical gospel heritage. Turn again to doing justice and loving mercy, as commanded by the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. The book of Genesis (or even older, the pre-Jewish book of Job) is a good place to start. We all have a tribal subconscious. Our authentic genetic identity is really in the humble ground of kinship or tribe or reproduction. [see]

Freud commented that we are an iceberg, which floats "with only one seventh of its bulk above water."

The genius of Freud is that he directs our gaze inward. We must look within for answers. We must look within for the truth that will set us free. The interpretation of dreams, of our most personal myths and narratives, is not a bad place to begin. The theology of Christendom aimed at "objectivity" and "certainty" and tried to hammer down the specifics of a definition of "God." [Link to sacred-texts.com]

But a humbler wisdom contents itself with the lowly realm of the subjective, with doubt and inexactness, with human struggle and weakness and need. Like the book of Genesis, and truly most of the heroes of the Bible, human character shies through with the authentic flavor of flesh-and-blood humanity.

Jesus didn't teach go-to-heaven; he taught Kingdom of Heaven.

Put not your trust in princes, nor in the son of man, in whom there is no help. His breath goeth forth, he returneth to the earth; in that very day his thoughts perish. [Ps 146: 3,4]

As Freud's theory evolved, he came to propose what he referred to as the 'death instinct' as a counter-part to the 'life instinct' (sex). Anthony Storr describes this death concept (thanatos) as the ultimate expression of the Nirvana principle, of the organism's striving to reach Swinburne's 'The Garden of Prosperpine' -- where no stimuli from either within or without disturb its everlasting peace.

Then star nor sun shall waken,

Nor any change of light:

Nor sound of water shaken,

Nor any sound or sight:

Nor wintry leaves nor vernal,

Nor days nor things diurnal;

Only the sleep eternal

In an eternal night.

Jews in Palestine and Native Peoples in Western Hemisphere -

Interesting discussion - by yankton Lakota elder Vine Deloria

Strange correspondences - chosen peoples & the ocean between - lost tribes of Israel : so-called "Indians" - by Simon Wiesenthal

noli foras ire, in teipsum redi; in interiore homine habitat veritas

Don't seek truth externally, return to yourself, the truth dwells within.

St. Augustine

What do you think?

Am I on the right track?

Bob Shepherd

Bob Shepherd with some pizza pals, 2008

Look inside - and find God there

ATONEMENT

friend me (facebook)

|

Feisty journalist commentator Andy Rooney wrote a column in 1992 that posited that it was "silly" for Native Americans to complain about team names like the Redskins, in which he wrote in part, "The real problem is, we took the country away from the Indians, they want it back and we're not going to give it to them. We feel guilty and we'll do what we can for them within reason, but they can't have their country back. Next question." |

last save 12.23.11

last save 03.31.15